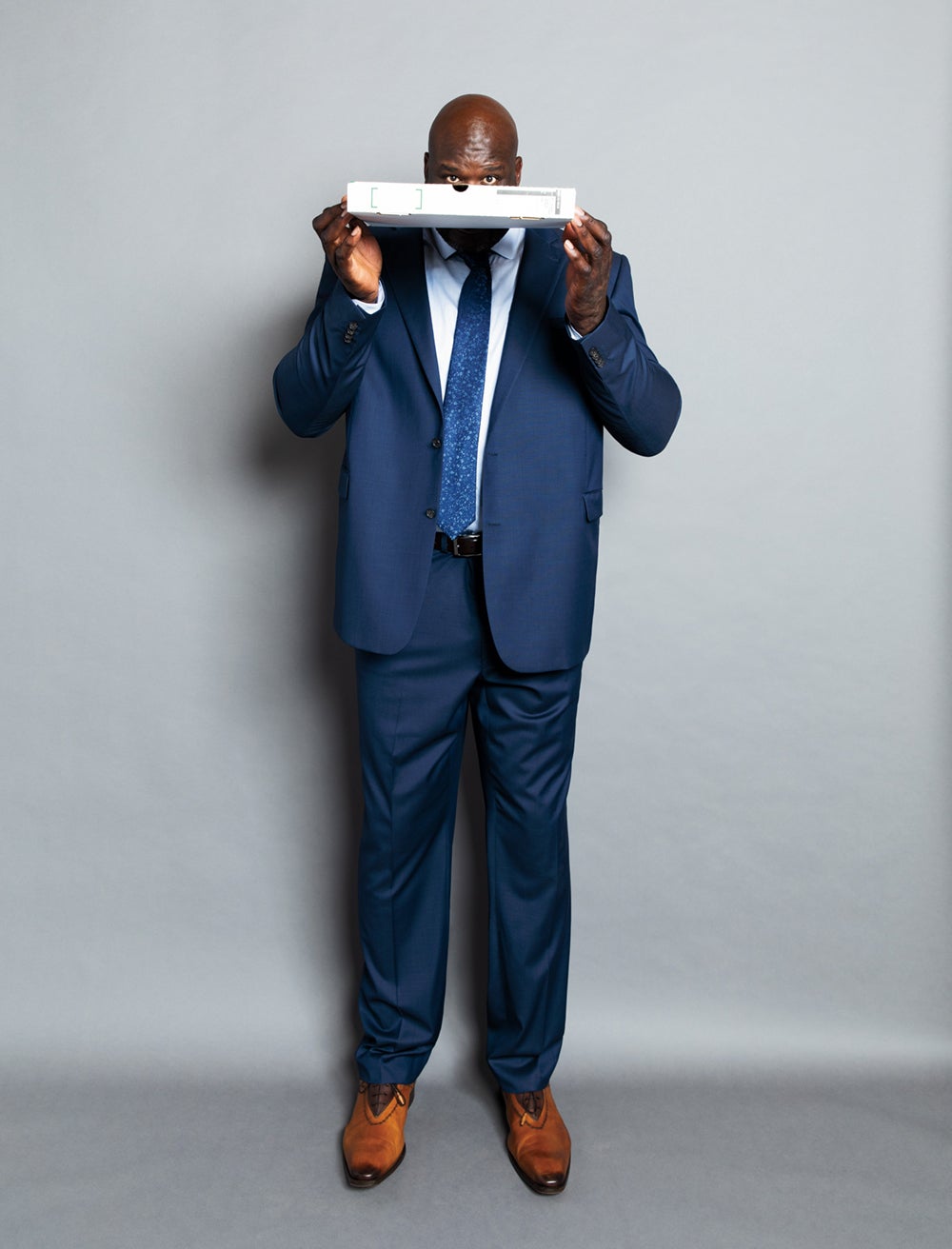

How Shaq Is Bringing Fun Back to Papa John's The basketball legend is the franchise's new brand ambassador. He's got his work cut out for him -- but Shaq's never been afraid of a challenge.

By Clint Carter

This story appears in the July 2019 issue of Entrepreneur. Subscribe »

Like most of its stores, the Papa John's on Wells Street in Milwaukee is primarily a carryout and delivery operation. The lobby fits only four chairs. So when 30 people crowd in, as they do on a recent Thursday afternoon when Shaquille O'Neal shows up for an impromptu pizza party, the sleepy joint suddenly feels like a nightclub.

"Shaq! Sign my shirt!" screams a grown man in a blue polo.

"Sign mine, too!" echoes one of the store's cooks.

Outside, people are pressing their noses against the plate-glass window as a man snaps a picture of his blond-headed son standing next to the 7'1" NBA Hall of Famer. But the dad's hand is shaking so violently that the few photos he fires off turn out blurry.

"Why are you shaking?" says O'Neal. Then, "You guys want pizza?"

Related: Former NFL Star Jason Avant Has a New Career -- In Trampoline Parks

Lunch is on O'Neal today. His visit is tied to his new role as a Papa John's brand ambassador, but the relationship runs deeper than the paid spokesman positions he's held with Buick, Gold Bond, Icy Hot and dozens of other companies. As of earlier this year, O'Neal is also a Papa John's franchisee and one of 10 executives serving on the company's board of directors. That gives him an honest stake in the brand. And in turn, Papa John's gets a genuine -- and, equally important, symbolic -- turn away from its past two nightmarish years.

The brand's misfortunes have been widely covered in the press. It began in 2017, when the company's namesake, founder, and then-CEO, John Schnatter, jumped hard into the country's divisive culture wars. Then in 2018, he was accused of using racist language. A large, noisy, messy schism ensued, which separated Founder John from Papa John's. Sales tanked. In August 2018, Papa John's stock hit a low of $38.05, down more than 50 percent over the year prior, and same-store sales for the quarter dropped nearly 10 percent.

Investors and fans alike have been wondering ever since: Can a brand like this recover? Shaq is a big part of the answer. He is the rare universally beloved celebrity in America, and he represents everything the brand wants to return to -- joy, inclusion, and a love of pizza.

And, oh, does Shaq love pizza. By his telling, he fell in love with Papa John's in college. None of the other brands met his standard. "I don't like thin crust, I don't like BS cheese, and I don't like crust with seven ingredients," he says. (Papa John's crust uses only six ingredients -- a recipe that will survive from the John Schnatter era.) That's why he was eager to buy into some Papa John's locations.

"Right now, I own 10," he says.

Uh, wait -- according to Papa John's, he owns nine.

"Nine, 10, what's the difference?" O'Neal says. "I thought I had 10. Now I have to go buy another store."

As the face of Papa John's, John Schnatter had one main benefit: authenticity. He was the guy. The name on the box! But like many founders who put themselves on TV -- say, Jim Koch of Sam Adams and Bob Kaufman of Bob's Discount Furniture -- he was also awkward on camera. Schnatter always seemed like a man who tried to look fun, rather than a man who actually was.

Related: 7 Tips to Take Your Personal Brand to Celebrity Status

O'Neal serves as a different model. At an early age, he realized the financial power of joy. Then he fully embraced it.

It first clicked with O'Neal when he was an NBA freshman, at the age of 20. He had a basketball career ahead of him but was already thinking past it -- inspired by Magic Johnson's career pivot into business. How, O'Neal wondered, could he leverage his own rising celebrity? Then he found an unlikely muse: Spuds MacKenzie.

You remember Spuds, right? The dog from the Bud Light commercial? When O'Neal saw Spuds on TV, he thought, Hey, I could do that. "Why do people like this ugly-ass, Little Rascals looking dog?" O'Neal says he asked himself. "Because his commercials are fun." Spuds wore sunglasses and a Hawaiian-print shirt. According to his commercials, he was a "party-loving, happening dude."

And O'Neal thought: If I ever get the chance to market myself, it has to be on that. There always has to be humor, and there always has to be something that makes people remember. In that moment an alter ego was born: O'Neal dubbed himself the Doctor of Fun.

Soon after, he picked up a Dummies Guide to business and discovered a chapter on joint ventureship. He liked what he read. Here was a model that would essentially allow him to be the entrepreneurial version of a slam-dunk guy -- the same role he played on the court. The coach calls the play, and the point guard brings the ball up the court. "Then throw it to me," O'Neal says, "and I know what to do with it."

When the Doctor of Fun -- an actual doctor, by the way, since he received a doctorate in education from Florida's Barry University in 2012 -- started making business decisions, he did so in the spirit of Spuds. Instead of a basketball video game, he came out with a wackadoodle street-fighting game called Shaq Fu. In the movie Kazaam, he played a genie liberated from a boom box. He once turned down the opportunity to be on a Wheaties box. Too plain! "I told my people, "Call Frosted Flakes or Fruity Pebbles,' " he says. (In 2015, he did indeed make the Fruity Pebbles box.)

Whatever he put his name on, he wanted it to be widely accessible. O'Neal once had a Shaq shoe with Reebok, but after a mother outside a basketball arena told him it was too expensive, he launched a budget line with Walmart. Then he retired his line of upscale modern-cut suits to launch a big-and-tall line with JCPenney.

For his first foray into food, O'Neal considered buying a McDonald's franchise. He soured on the plan after discovering he'd have to attend McDonald's Hamburger University -- where, famously, the brand initiates owners by working them at every station of the restaurant. But he found other ways into the franchise world. A friend of a friend at a party in Beverly Hills mentioned that he was looking for investors for his new burger chain, Five Guys. O'Neal would go on to own 27 stores, though he sold them. However, he still owns an Auntie Anne's and a Krispy Kreme, which he calls "the number one Krispy Kreme in the world." (He owns a few nonfranchised restaurants as well.)

But still, O'Neal is always looking for something new. And last year, as it so happened, Papa John's was looking for something new, too.

Today Papa John's operates in all 50 states and 48 countries. Between its franchise and corporate stores, the company counts 5,336 locations and 120,000 employees. It's the third-biggest pizza delivery chain in the world, behind Domino's and Pizza Hut. But it started with an American origin story as humble as any you've ever heard.

It was 1983 in Jeffersonville, Ind., and John Schnatter, fresh out of college and 23 years old, sold his Camaro to purchase a pizza oven. Then he took a sledgehammer to the walls of a broom closet in the back of his father's bar, set up a kitchen, and began crafting his Papa John persona. In 1986, he sold his first franchise. In 1993, the company went public. And in 2009, Schnatter tracked down his old Camaro and bought it back for $250,000.

Schnatter was the undisputed leader and face of the company he built. In 2010, with some 3,500 stores to its name, the company signed on as the official sponsor of the NFL, which amplified Papa John's already huge visibility. Quarterback Peyton Manning became a franchisee and for years would appear in commercials with Schnatter, tossing a football like old chums. The company rode rocket-ship growth, with 14 years of positive or flat same-store revenues, a 22 percent increase on earnings per share, and record sales of $3.7 billion globally in 2016.

Then came November 2017. The news was everywhere: While trying to explain lackluster sales -- Papa John's numbers were lower than expected -- Schnatter chastised the NFL management for allowing its players to continue kneeling. At the time, kneeling for the national anthem was among the hottest-debated subjects, dividing America along predictable political lines. "We are totally disappointed in the NFL and its leadership," Schnatter said, adding that the problem should have been "nipped in the bud a year and a half ago."

Related: Here's How Lenny Kravitz Creates Something Out of Nothing in Business and Art

Suddenly Papa John's learned the lesson that almost every major brand does when it picks a political side. Nobody wanted to talk about Papa John's vine-fresh sauce or six-ingredient pizza dough. They instead wanted to talk about Schnatter. The company's fourth-quarter sales dropped 3.9 percent, effectively flattening a year of modest gains, while franchisees across the nation began distancing themselves from their founder.

"We're not John Schnatter," says Melanie Langford, who runs 11 Papa John's stores in Alabama. She and her team relayed that message over and over on phone calls to churches, schools, and other corporate account holders within the community. "We're the local guys. We employ people locally, and we support local families."

Two weeks after the initial comment, and after the neo-Nazi site Daily Stormer called Papa John's the "official pizza of the Aryan master race," the brand finally responded. It apologized on Twitter and gave neo-Nazis an emoji middle finger. But by then, damage had been done. "What Schnatter said should have been corrected by public relations immediately," Langford says. "Instead they sat on it."

The PR fire continued to blaze. In January, Schnatter stepped down from his role as CEO. Papa John's and the NFL ended their relationship, and Peyton Manning sold his stake in 31 stores. Then the bottom fell out. Forbes published a claim from Papa John's former creative agency alleging that Schnatter had used racist language, including the N-word, during a call. In response, Schnatter stepped down as the company chairman. But that didn't soften the blowback.

"We're still dealing with the NFL thing, and now this?" says Kenyatta Theodore, an African American Papa John's franchisee who at the time operated three stores with her husband, Herb, in New Orleans. "It was like someone had punched me in the stomach."

Theodore began hearing customers say they didn't want to support Papa John's -- or rather, they didn't want to support Papa John Schnatter. During a teacher appreciation day, one teacher refused her free slice on moral grounds. "Most people don't even know that we own our stores," says Theodore. "We never felt like we had to tell them before." When people started asking why they didn't leave the company and its controversial founder, Theodore replied: "John Schnatter does not represent me. I represent myself. I'm a franchisee, and this is my store."

Related: Why Rapper-Turned-Entrepreneur T.I. Says a Hustler Needs to Be Patient

Schnatter, for his part, maintains that his intended use of the N-word was to point out that another company, one that his agency wanted him to partner with, had used that word in the past. A power struggle ensued within Papa John's, and Schnatter was evicted from the office. He launched a website to share his side of the story and filed two lawsuits, both of which have since been dropped. While Schnatter still owns about 20 percent of the company, he now has nothing to do with the daily operations, say company reps. And he's been rapidly selling off his shares.

In 2018, during the corporate battle, 186 franchise stores shut down. One of those belonged to Kenyatta and Herb. "It really affected us tremendously," Theodore says. "We went from one of the highest-ranked stores to the bottom."

Papa John's installed a new CEO to solve the problem. He was Steve Ritchie, a 23-year veteran of the company. And nervous franchisees wanted to see action -- fast.

The moment was not lost on Ritchie.

"With most brands, there aren't tremendous shifts in sentiment year over year," he says. The same could not be said of his. "We had a significant decline in sentiment." There was no time to waste -- he needed to calm the company's nervous franchisees and make every change necessary to return that public sentiment back to where it was before. It wasn't an especially enviable role to step into, though it did have at least one upside: As the cleanup man, there was no need to sugarcoat anything. "It's going to be a struggle, but just give me time," he told Theodore when they met. "I'm going to do my part to get us back where we need to be."

Papa John's offered financial assistance to keep its franchisees afloat. It spent $15.4 million in royalty relief and $5.8 million to give the brand a new image -- the company wanted Schnatter's face off all branding. It added $10 million to the national marketing budget, and then paid $19.5 million in legal and professional fees tied to a voluntary audit of the company's culture and a strategic review.

Related: Lacrosse Star Paul Rabil: I'm 'Risking Everything' to Change the Sport

Then the brand announced a partnership with Starboard Value, an activist investing group that turned Olive Garden around by taking over the entire board of directors for its parent company, Darden. With $250 million from Starboard, Papa John's began paying down debt, and it vowed to continue providing financial assistance to franchisees and continue paying out marketing and legal expenses -- a burden that will run between $30 and $50 million this year.

Ritchie is also well aware of the audience Papa John's needs to court the most: nonwhite consumers, who were most offended by Schnatter's scandals. So the brand is reaching out to them overtly. In a new commercial featuring employees of different skin tones, for example, one store owner says, "You've heard one voice of Papa John's for a long time." Then a second owner completes the thought: "It's time you heard from all of us."

Papa John's has begun forming new partnerships with a diverse mix of suppliers and creative agencies, including those owned by African Americans. Through its newly formed charity, The Papa John's Foundation, the company made a half-million-dollar donation to North Carolina's Bennett College, a historically black female college, and a quarter-million-dollar donation to the Boys & Girls Club. The new Dough & Degrees program, launched with Purdue University Global, allows employees to earn college degrees with free or reduced tuition costs, and a new position -- the chief of diversity, equity, and inclusion -- is overseeing system-wide diversity training for all Papa John's employees.

But there was still an open question: Who should replace Schnatter as the new face of the brand? Who could appeal across demographics, while also showcasing Papa John's new commitment to diversity?

And then Ritchie got a call from a certain NBA Hall of Famer.

In the past, Papa John's knew exactly what it would do for the Super Bowl, the year's biggest day for pizza sales. It would be running ads during the game, and showing up at official events. But the scandals of the past had shattered that relationship. So as Papa John's looked for a new way to partake in the game this past February, it learned about a party O'Neal was hosting. He called it Shaq's Fun House, and it featured performances by T-Pain, Lil Jon, and Cirque du Soleil.

Papa John's signed on as a Fun House sponsor. To Ritchie's surprise, O'Neal asked him to fly down early for a meeting. "Before I could give him my sales pitch of having additional involvement with the brand, Shaq said, "I love your story,' " says Ritchie. " "I'd love to be able to talk about how I can become a franchisee.' "

Ritchie took the idea back to Papa John's, and the company hatched a bigger idea. What if O'Neal joined the board? It was a long shot, and possibly a risky play. But it felt right. Papa John's was hemorrhaging fun, and O'Neal, the self-proclaimed Doctor of Fun, was just the guy to suture the wounds. Plus, he checked all the professional boxes. "Shaq obviously fits the bill of being a diverse candidate, but he's also an entrepreneur," says Ritchie. "We wanted to find someone who had franchising experience in the QSR industry, and we also wanted to find someone who knew how to connect to consumers."

The deal came together fast. O'Neal signed a three-year brand ambassador deal for $8.25 million in cash and stock, and his role on the board was designed to help him shape the company's culture. (He's the only African American on the board.) He also took a 30 percent stake in nine stores (not 10 yet!) in Atlanta, which he wanted to "Shaq-imize" -- adding a building-size signature on the exterior, and his size-22 footprints leading up to the counter.

Six weeks after the Super Bowl, Papa John's announced the partnership. It led to what seems like the best press Papa John's has had in years, and has continued over the months as the relationship takes shape -- O'Neal showing up at stores, say, or Ritchie revealing that a Shaq-themed pizza is in the works. Investors seem happy as well. "He's like Oprah," says Ivan Feinseth, an analyst covering Papa John's for Tigress Financial. "Everybody likes Oprah, and everybody likes Shaq. They were lucky to get him."

But the best reviews seem to be coming from the franchisees.

As a spokesperson, O'Neal is a big upgrade from Schnatter, some say. "John's really smart, and his tenacity built Papa John's, but he's a bit socially awkward," says Langford, the franchisee from Alabama. "He comes across as quirky." O'Neal, on the other hand, is as comfortable with crowds as he is with a basketball. "When he smiles, his whole face smiles," she says. "So while I kind of miss the NFL, I'm really happy to have Shaq."

It's early days, of course, and even O'Neal can't turn around a brand in a few months.

Store traffic is still hurting. While Domino's and Pizza Hut posted positive and flat first-quarter comps this year, respectively, Papa John's was down 6.9 percent. And the brand's franchise association is eager for tangible results. "Sales have gone down, and franchisees have been suffering," says Robert Zarco, an attorney representing the Papa John's Franchise Association (PJFA). "That's something that will not be repaired immediately. I don't think [corporate leadership] is doing enough, and I don't think they're doing it fast enough." (The PJFA president, Vaughn Frey, declined to comment.)

Papa John's corporate, however, expects sales to rebound by the end of 2019. "This year is all about doing the work," says Ritchie. "We would hope at the tail end of the year we're starting to show some monthly positive numbers, and next year will be a time of celebration."

But one number is already rising: Consumer sentiment is up double digits, says Ritchie. And he attributes part of that to O'Neal. "He's very serious about the work he's doing here," the CEO says, "but at the same time, we need a little bit of fun."

Back at the store in Milwaukee, O'Neal orders eight pizzas, split among sausage, pepperoni, and cheese. The store supervisor, Scott Hermanson, shouts over the crowd: "Is everyone here for Shaq, or can I help anyone?" Nobody seems to hear him, so he gives up, steps around the counter, and snaps a few photos with the star.

O'Neal keeps one pie for himself and doles out the rest to the crowd, making sure that college kids eat first. Then, pizza in hand, he plows through his crowd of fans as they continue to shower him with love and gratitude, with one guy shouting at his back, "Thanks for being real, baby!"

There's been one board meeting since O'Neal signed on, and the value of this new relationship is still to be revealed. But O'Neal, who called himself Superman during his NBA days, seems to have a particular superpower here: He can make people live in the present, not the past. When he walks into a store, everyone rushes to him. When he talks, people light up. And by attaching his name to Papa John's, he's beginning to pry the brand away from its messy past.

In fact, O'Neal won't even refer to Schnatter by name. He just calls him "the old guy" -- part of a bygone era.

"When the old guy said what he said, not only did it hurt his business, but it hurt the franchisees' business, too," O'Neal says. "But now I want to let people know that we accept everybody, we include everybody, and we love everybody."