Finding Customers Ahead of a Startup Launch

Lining up buyers in advance of launch can be challenging for a new company. But finding the right ones–and capitalizing on them–can go a long way toward ensuring early success.

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

When Ariel Seidman left Yahoo last year to start his own tech company with two former co-workers, he knew that success out of the gate would hinge on having some big-name customers already lined up. So he spent most of his time in Silicon Valley coffee shops or on conference calls explaining the idea behind Gigwalk–harnessing the power of millions of iPhone users to create what the company likes to call “the first on-demand mobile work force”–and gauging the market need for its services.

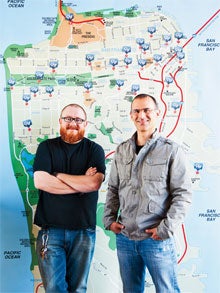

By the time Gigwalk launched in May, Seidman–along with co-founders Matt Crampton, the chief technology officer, and David Watanabe, the chief of design–had lined up TomTom, the Amsterdam-based maker of satellite navigation devices, and MenuPages, the online restaurant directory.

“It took on a life of its own after we started going out there and talking to people about it,” Seidman says. “When you actually launch, having customers you can talk about gives confidence to other potential customers. They figure, ‘If a brand like TomTom is willing to use this new company, then I’m willing to use it as well.'”

Based in Mountain View, Calif., Gigwalk relies on iPhone users across the country to take pictures and provide data for clients. The workers, or Gigwalkers, find gigs by downloading the Gigwalk app. Gigwalkers earn from $3 to as much as $90 per gig, and their pay goes up once they establish their Gigwalking credentials.

Seidman and company figured early on that the best customers would be local business sites and mapping companies–staples in the online business world. But the more they discussed the concept, the more they realized Gigwalk could serve a far wider market. An ad agency wanted to compile a database of billboards in Manhattan; the state of Florida wanted to verify its wireless and broadband coverage. Financial services firms, travel and real estate offices, app developers–all thought Gigwalk could work for them.

There’s no single method for startup hopefuls to generate customer interest before launching their business. Seidman’s experience illustrates the value of the pre-launch period for drumming up support from customers and investors. Perhaps most important, it shows how entrepreneurs can fine-tune their business prior to launching, helping them better serve their customers right out of the gate.

That’s a lesson Michael Burcham holds dear. Burcham directs the Nashville Entrepreneur Center, a public/private partnership that provides entrepreneurs with office space and a team of 100 mentors to advise them in all aspects of the startup process. Burcham’s approach to launching a business can be summed up in three words: refine, refine, refine.

“It’s universally true for all entrepreneurs, no matter how good we are: When we put our business plan together, if true north is a perfect plan, all of us are off at least 10 degrees,” Burcham says. “As a startup, our job is to close that gap as soon as possible.”

At the center, entrepreneurs spend their first two weeks trying to identify a dozen potential customers. By the third week, Burcham has them arranging meetings. From there, the pre-launch process becomes an exercise in fine-tuning the business so that it provides just what its customers will need.

“We really focus a lot on customer segmentation,” Burcham says. “Who is this solution for? What pain is this solving? As potential customers give you feedback and you keep coming back with revisions, you get buy-in to the customer input. If it’s done well, that prospective customer is very close to becoming a signed-letter-of-intent customer.”

Burcham worked closely with Jackson Miller before Miller started Bizen, a Nashville, Tenn.–based software service that provides retailers with real-time cash register reports. Miller studied jazz and philosophy in college but left before getting a degree. He grew up around computers (“I just had an aptitude for it,” he says), and after he left school he worked as a business intelligence consultant and developed software for several startups.

Miller also is a partner in two Plato’s Closet franchises, which sell used name-brand clothing. Like other franchisees, Miller relied on traditional point-of-sale reports generated from the stores’ cash registers. But the reports didn’t give him the performance indicators he really needed. So Miller designed a software tool that spots trends and sends text messages that alert users to key events, such as when a cash register doesn’t balance or when the labor percentage of sales gets too high.

“What Bizen does is integrated with the point of sale,” Miller says. “In the franchise model, it allows you to benchmark against other stores in the franchise. It allows me to be a more involved owner even when I’m not in the store. I like to say we redefine ROI as return on involvement.”

At the entrepreneur center, Miller distilled his customer base with the help of Burcham and the team of mentors. Miller raised $350,000 in funding, and in May, shortly before launch, he researched the market for Bizen at franchise trade shows in Las Vegas.

“We could work together to come up with hypotheses of what the need might be, but only through talking with the target market–our customers–could we understand where the need really was,” Miller says, “By having those conversations with customers before you build the product, you can get closer to true north more quickly, without wasting time and money on guesswork.”

Laura Adamson went through a similar process to fine-tune her online shopping site, Styleoutsidethebox.com, before she launched June 1. After graduating from Penn State with a business degree, Adamson managed three pop-up stores in Manhattan before moving back to Lancaster, Penn., and striking out on her own. Her site features limited-distribution clothing, jewelry and accessories–in other words, stuff you won’t find at the mall–made by designers from London to New York City to Toronto. A jury team approves everything that goes on the site, Adamson says, and she only partners with designers who guarantee their work. “We’re trying to bring back that relationship between the customer and the creator of the jewelry,” she says.

Before launching, Adamson relied heavily on social media like Twitter and Facebook, sending as many as 10 updates per day. She quickly reaped the benefits, as designers and shoppers retweeted her posts even before the site went live.

“I really didn’t want to start my social media until we launched the site,” Adamson says. “You know what? I wish I’d started it sooner.”

At Gigwalk, Seidman, Crampton and Watanabe ran pre-launch trials of their own. Once Seidman convinced a potential client of the merits of Gigwalk’s business model, the company would run a small test of 30 to 50 gigs. If the test went smoothly, the company would try a slightly larger test. The trials showed prospects the value of Gigwalk’s services and gave the company the opportunity to fix any glitches. “Now we’re dealing with tens of thousands of gigs for individual companies,” Seidman says.

As customers began to sign on with Gigwalk, investors followed. The company raised $1.7 million from venture capitalists, including Reid Hoffman, the co-founder of LinkedIn, and Jean-Francois “Jeff” Clavier, the founder and managing partner of SoftTech VC in Palo Alto, Calif.

“It’s always an issue for investors,” Clavier says. “How many clients do you need to want to invest? In the case of Gigwalk, I was happy to take a chance because it made so much sense for me. In this market, if you wait, you play a losing game. If you want to win, you basically come with your checkbook and say, ‘OK, I like this. How much?'”

And that, of course, is music to the ears of any startup entrepreneur.

What I Learned From My Customers

Gigwalk was halfway through an assignment when its client, online restaurant directory MenuPages, asked for a meeting with CEO Ariel Seidman. The company had hired Gigwalk to compile data on 300 Los Angeles restaurants–hours of operation, minimum delivery fee and iPhone photographs of the menus. But some of the photos were coming in blurry or with menu items cut off. The subpar images were traced to early-model iPhones being used by some of Gigwalk’s contributors–a mobile work force known as Gigwalkers.

So Seidman refined the terms of the MenuPages gig, requiring Gigwalkers to use the iPhone 4–then Apple’s newest model–to photograph the rest of the menus. MenuPages was pleased enough with the results to order gigs in Chicago, Miami, Boston and San Francisco.

“They pushed us hard on a lot of stuff,” Seidman says of MenuPages. “They told us honestly what was working and what wasn’t working. They made us better. They made the product better.”

As Seidman discovered, customers can teach you a lot about how to improve your business, especially during the critical pre-launch phase.

Laura Adamson learned that lesson during the three months she spent preparing a website for her new online shopping business. As a trial run, she watched 10 would-be shoppers navigate the site, checking to see if they encountered any trouble. They did. But Adamson was able to make adjustments and further trouble was averted.

Before Jackson Miller launched Bizen, he planned to provide end-of-day cash register reports to his retail clients. Not good enough, they told him. “What I learned from customers is that it’s more actionable if, in the middle of the day, a text message can tell them if something is out of whack,” says Miller, who reprogrammed Bizen’s software to deliver more up-to-the-minute reports.

Miller also learned an unexpected lesson from his pre-launch discussions with potential clients. “Not only did they teach me what to build,” he says, “they taught me how to sell it.”

When Ariel Seidman left Yahoo last year to start his own tech company with two former co-workers, he knew that success out of the gate would hinge on having some big-name customers already lined up. So he spent most of his time in Silicon Valley coffee shops or on conference calls explaining the idea behind Gigwalk–harnessing the power of millions of iPhone users to create what the company likes to call “the first on-demand mobile work force”–and gauging the market need for its services.

By the time Gigwalk launched in May, Seidman–along with co-founders Matt Crampton, the chief technology officer, and David Watanabe, the chief of design–had lined up TomTom, the Amsterdam-based maker of satellite navigation devices, and MenuPages, the online restaurant directory.

“It took on a life of its own after we started going out there and talking to people about it,” Seidman says. “When you actually launch, having customers you can talk about gives confidence to other potential customers. They figure, ‘If a brand like TomTom is willing to use this new company, then I’m willing to use it as well.'”