Who Counts As an Entrepreneur? (Opinion)

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Guest op-ed contributor Scott Shane is a professor of entrepreneurial studies at Case Western Reserve University. He writes about entrepreneurship and innovation management, among other things.

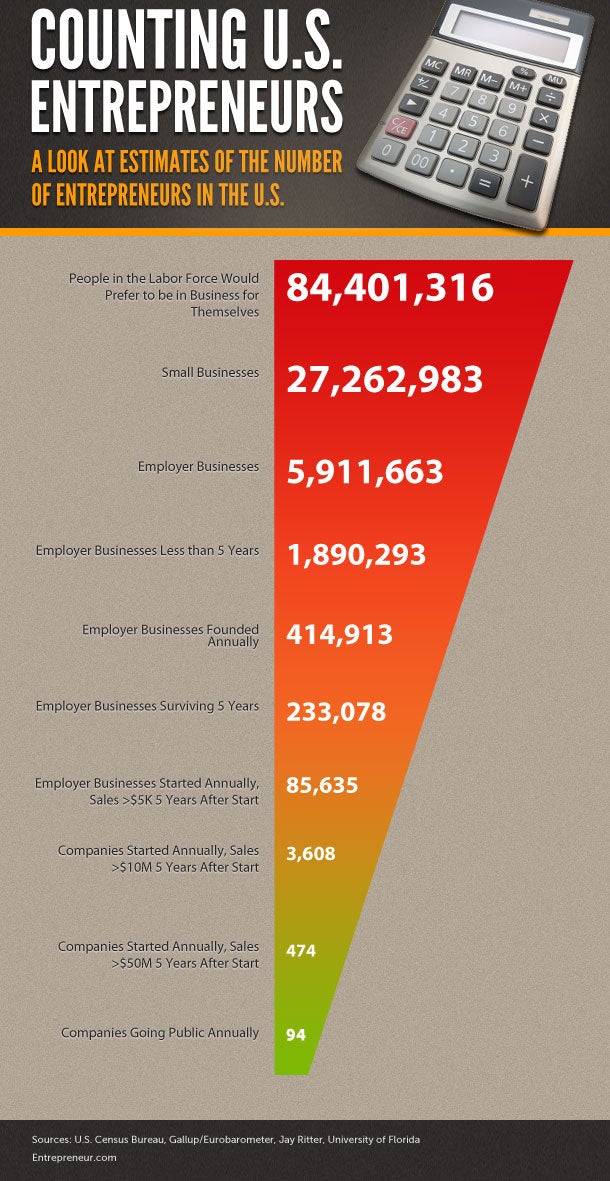

How many entrepreneurs are there in the U.S.? The statistics show that the number is somewhere between 50 and 84 million.

Before you think this is the beginning of a joke about economists, permit me to explain. The number of U.S. entrepreneurs depends a great deal how you define “entrepreneur.”

At the broadest end of the spectrum, some people call anyone who would prefer to be in business for themselves an “entrepreneur.” Extrapolating to the U.S. labor force from a recent Gallup survey of a representative sample of U.S. adults about their preference for self-employment, I estimate that more than 84 million Americans would prefer to work for themselves than for someone else.

Related: Seven Ways Solopreneurs Can Grow a Home Business

Of course, most of them haven’t done anything to achieve this goal. And a pretty portion of the labor force has other desires they haven’t yet achieved, like becoming a multimillionaire. So maybe we want to go with something a little more than what Americans would prefer.

What about actually having a business? There were more than 27 million small businesses in the U.S., according to a Census Bureau estimate from 2008, the latest year that data are available.

But many of those businesses don’t employ anyone. And some people say that you can’t be an entrepreneur if you’ve never met a payroll. So maybe we need to limit our numbers to businesses that have employees. The Census Bureau reports that there were just shy of 6 million small businesses with employees in 2008.

Related: How to Make Employee Training a Winning Investment

Of course some might ask: How old can a company be before it’s no longer a start-up, and its founder is no longer an entrepreneur? Some small businesses are 100 years old and their founders are long dead. So perhaps we want to put a limit on how old a small business can be before we have to give up counting its founder as an entrepreneur. Census data show that around 1.9 million small businesses are less than five years old.

Okay, but some people say that continuing to run a business that has already been started isn’t entrepreneurship. Starting a business is really what should count here. If we limit entrepreneurship to new businesses with employees started the last year, we are down to a little over 400,000 companies.

Now it’s true that anyone can start a business. What many people think makes a person an entrepreneur is running a start-up successfully. Since Census data show that only about 230,000 new businesses with employees that are started every year survive to age five, perhaps we want to limit the term “entrepreneur” to those people who manage to keep their businesses going that long.

But some people think just keeping a business alive isn’t enough to earn the label “entrepreneur.” The company has to have some healthy revenue after five years for the founder to earn the right to use the term. If we limit ourselves to only those new employer businesses that have $500,000 or more in annual sales five years after starting we are down to about 86,000 companies.

Of course, generating $500,000 in annual sales five years after starting won’t get you on the cover of many magazines with the caption “this is a true entrepreneur.” That honor is usually reserved for people who really grow their businesses. Maybe we should limit the label to those founders whose businesses achieve the level of sales that many accredited business angels think is attractive — $10 million in five years. That brings us down to less than 4,000 new companies started every year.

Related: A Lesson in Growing Your Brand from the ‘Pawn Stars’

But many of our VC friends don’t think much of the angels’ target of $10 million in sales in five years. They are looking for companies that can reach $50 million in sales in five years. If we limit the term “entrepreneur” to the people who reach that goal, we are down to less than 500 new companies started every year.

And then there’s going public. A lot of people would agree that a person who can take a start-up public really is an entrepreneur. But there aren’t too many of them around. Last year 94 companies went public in the U.S. last year, excluding American Depository Receipts, according to finance professor Jay Ritter of the University of Florida, who maintains initial public offering records.

We should also knock this number down a little. Some of these IPOs were old companies. Others were buyouts. Still others were founded by people outside the country. Do that and we can safely conclude that last year about 50 under-20-year-old-non-buyouts founded by Americans went public.

Clearly people define “entrepreneur” differently, which leads to the wildly varied estimates of the number of entrepreneurs in the country. This is a problem for several reasons, but let me just give you one. Suppose you want to design a policy to help “entrepreneurs.” What kind of program you design depends on your definition of the term — a program to help the 84 million people who would prefer to be self-employed is going to look very different from one to help the founders of young companies that just went public.

Identifying the “correct” definition matters a lot less than simply getting agreement on what the term “entrepreneur” means. We can’t have a meaningful discussion of how to help entrepreneurs, how successful entrepreneurs are, the contribution entrepreneurs make to the economy, or a host of other topics if we all define the word differently.

Guest op-ed contributor Scott Shane is a professor of entrepreneurial studies at Case Western Reserve University. He writes about entrepreneurship and innovation management, among other things.

How many entrepreneurs are there in the U.S.? The statistics show that the number is somewhere between 50 and 84 million.

Before you think this is the beginning of a joke about economists, permit me to explain. The number of U.S. entrepreneurs depends a great deal how you define “entrepreneur.”