The Future Is…Fungi?: This Biotech Company Transforms Mushrooms Into Luxury Materials Used by Hermès

At MycoWorks’ “Freedom of Creation” exhibit, co-founder and chief of culture Sophia Wang discusses how artistic beginnings launched a biotech company that’s churning out fungi-fueled materials fit for “a prince’s yacht” — and driving sustainability and diversity in the corporate world.

On a rainy New York City day in late March, sheets of what appear to be leather hang on the wall of one Chelsea art gallery, sleek black draped over tawny and beige. “I like to put out these samples because there’s so much variation that we can design for,” MycoWorks co-founder and chief of culture Sophia Wang tells Entrepreneur. “You could go for something very homogenous, or you could go for something that actually brings out the signature unique grain.”

A table sits laden with traditional leatherworking tools: sharp, wooden-handled instruments, a heavy press poised to set snaps and rivets. The tools, Wang says, allow artisans to “seamlessly” manipulate the material as they would traditional leather. Because, as much as the sheets on the wall look and feel like the real deal, they aren’t made from animal skin at all — though they are grown from living material: fungi, to be exact.

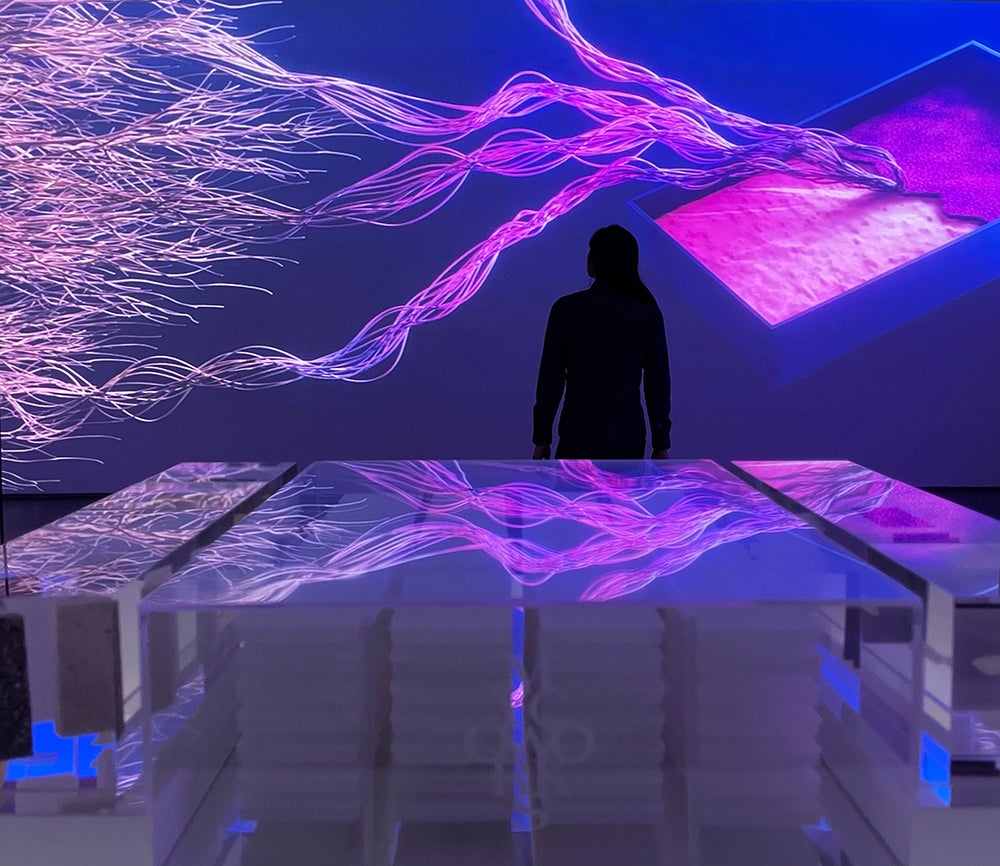

MycoWorks’ interactive “Freedom of Creation” exhibit tells the story of the biotech company behind Fine Mycelium, a natural, made-to-order material made from the root structure of reishi mushrooms. The company counts celebrities Natalie Portman and John Legend among its investors, and its mycelium material has already been adopted by major fashion houses such as Hermès. In fact, MycoWorks has outgrown its Emeryville, California pilot plant, which processes thousands of the mushroom-derived sheets per year; its new Columbia, South Carolina facility will process several million.

Despite its biotech designation, the company has artistic roots. Co-founder and San Francisco-based artist Philip Ross, also a chef and naturalist, first learned to forage for mushrooms in the woods of upstate New York. Later on, when he worked as a hospice caregiver in the midst of the San Francisco HIV crisis, Ross became familiar with the immune-enhancing power of reishi mushrooms and cultivated them for medicinal purposes. Inspired by the mushroom’s lush variety in form, texture and color, he ultimately began creating sculptures with the material.

“Making a high-value, beautiful object of desire made sense”

As global interest in sustainability continued to mount, Ross saw an opportunity to merge mycotecture (the term he coined in 2008, which refers to the art of designing and building with mycelium) with brand partnerships. He asked Wang, his long-time artistic collaborator, to launch a company with him, and she agreed. Initially, the pair considered using mycelium in its rigid form as a source for natural building materials, but they soon realized an even greater potential within the realm of sustainable fashion.

“We were looking at building materials, because the art objects had demonstrated that’s what you could make,” Wang says. “But as a small company, the per unit cost of competing with something like an engineered wood product or styrofoam is really challenging. You’d have to solve insane volumes for the margin. But with fashion, making a high-value, beautiful object of desire made sense with what we were offering.”

So that’s exactly what MycoWorks did. The company connected with footwear and fashion brands that were impressed by the mycelium material’s unique aesthetic qualities, customization potential and sustainable advantage.

For Wang, like Ross, the melding of art and science in pursuit of sustainability and new creative modes came naturally. “Both my parents were scientists, so I actually grew up sort of immersed in scientific-systems thinking and thinking about the world culturally and symbolically through art,” Wang says. “Phil and I both speak the art intersected with science language, and if you think about how innovation actually happens in any of those fields, it’s really about close creative attention to your material and bringing design thinking to what you’re trying to manifest.”

Related: How This Sister and Brother Co-Founded a $45.1 Million Revenue-Generating Sustainable Business

“It’s a very visual and sensorial experience…they’re actually working with the mycelium itself, because it’s alive”

In a separate room of the exhibit, a projected film wraps around three huge, blank walls, displaying the Fine Mycelium-creation process in all its glory. It all begins with the company’s two- by three-foot tray — its bioreactor. The tray’s sizing is very intentional, as the amount of material it produces fits perfectly into fabrication designers’ processes: just the right size to make a purse, for instance. But the organic material certainly isn’t limited by size; in 2016, MycoWorks proved the technology could replicate an entire animal hide.

MycoWorks’ chief operating officer Douglas Hardesty breaks the process down even further with the help of models. “We start off with this tray filled with wood, water and mycelium,” Hardesty says. “Three things. From there, we grow through the mycelium, and expand the number of cells into a full brick, which is white when it’s done. At that point, we add the first customization step, which is a textile, and it can be one of thousands of textiles.

“What we find is then we can amass different features and different profiles of the material based on what textile we use,” Hardesty continues. “So you’ll see everything from cotton and silk, beautiful silk like you’d use in a silk scarf, all the way up to Kevlar and wire mesh.”

From there, the mycelium enters its growth cycle. Many biomaterials on the market rely on fibers glued together with plastics, Hardesty explains, but MycoWorks’ mycelium is actually grown — cells intertwining with textile to create the sustainable material.

“Our Fine Mycelium experts spend their time with the product, really kind of having this conversation with the material where they’re talking and they’re smelling and they’re looking — it’s a very visual and sensorial experience for our operators, because they’re actually working with the mycelium itself, because it’s alive,” Hardesty says.

Once the fungal leather (or other textile) has the right physical characteristics, it’s time to harvest it. Hardesty says the process of removing the material from its substrate, the underlying layer on which the Fine Mycelium grows, is like “taking the frosting off the top of a cake.”

At that point, operators add a lubricant, similar to a lotion you’d use on your skin, effectively ending the growth phase and jumpstarting the tanning process. Like leather, Fine Mycelium can be altered with natural dyes and colorants, and finished to the customer’s specifications.

Related: Sustainable Fashion for Earth Day and Beyond

“This is like for some prince’s yacht or something”

In the next room, the breadth of Fine Mycelium’s potential is on full display. Phone cases, purse straps, wallets, belts and even the upper of an Oxford shoe line one of the tables, bordered by samples in vibrant metallics — rich burgundy, radiant green. Nearby, pieces in light blue and gold, the alternative textiles Hardesty mentioned, are also laid out.

“You can see the gold-like shimmer,” Wang says of one folded gold-mesh sample. “We joke about this one being the next-level luxury material. Not only do you want Fine Mycelium, but you also want Fine Mycelium with gold in it. This is like for some prince’s yacht or something,” she laughs.

Fabrics fit for a prince’s yacht and the fact that MycoWorks’ Fine Mycelium has already caught the eye of luxury-fashion-powerhouses like Hermès naturally beg the question of accessibility — is fungi the future for most people, or will the sustainable material be too cost prohibitive? Wang says the current volume of production and high demand for Fine Mycelium allow for a premium associated with the product, one comparable to other goods made of exotic animal skin, but there is an exciting vision for expansion.

“We’re in the process of making it available to as many partners as we can,” Wang says. “So right now we do have a premium on our product, but with establishing a factory where we can do millions of square feet in a year, and then potentially additional factories, we can actually address the market at many different price points.”

“You can triple the productivity, you don’t have to kill anything, and it has an identical hand feel”

The incredible demand at this point is easy to understand; not only does Fine Mycelium serve as a sustainable option with the look, feel and malleability of leather, but it also has properties that its animal-skin counterparts lack. Its strong, densely intertwined cellular structures resemble the triple helix of collagen, and it’s possible to split the material to just 0.2 millimeters, whereas leather can only be thinned to 0.4 millimeters.

Mycelium can also be used for products with stitchless construction. With leather, Wang says, attempts to fasten the material to itself are basically futile, “like when you get crazy glue on your skin. It’ll stick for a while, but eventually you can peel it off.” But with mycelium, a high-frequency-welding process, during which the fungal leather is bathed in electromagnetic waves, allows it to adhere to itself, making for major savings on labor and supplies. Additionally, mycelium can grow to three-dimensional form — shaping itself into a seamless object like a phone case, for example.

Mycelium’s vast customization potential also cuts costs on materials to an extent that’s not possible with traditional leather. “In traditional alligator or crocodile skins, only the spine section is used, so about 60% of the hide is wasted,” MycoWorks senior director of product strategy Wei-En Chang explains. “With our material, we’re using a roller embossing process, and we actually have three spine sections, so you can triple the productivity, you don’t have to kill anything, and it has an identical hand feel — it will take on the same patina as the reptile skin, and it’s just much better for the environment overall.”

“Diversity of thinking is what produces the most innovative solutions”

MycoWorks isn’t just revolutionizing luxury materials in the fashion industry; it’s also advocating for diversity in the corporate arena. “We’re doing what we can, being a microcosm of the world, which has its own structural dynamics,” Wang says. The company’s research and development team is led by women mycologists, and women also lead its process engineering and manufacturing team.

“Beyond empowering and hiring women, there’s a real ethos of diversity,” Wang says. “And in all the senses — not just identity-based diversity, but diversity of thought, expertise, professional experience and personal experience, which is tied to identity. I’m excited that MycoWorks has become a platform for us to really model that for other companies in the industry.”

Wang believes the artistic spirit present from the company’s early days has helped fuel MycoWorks’ forward-thinking philosophy. “I think the diversity of thinking that started with the company’s founding, an artist’s thinking within a material-science space, has carried over into the very diverse team that we’ve built,” Wang says. “Because I think diversity of thinking is what produces the most innovative solutions — and thinking across fields, like what’s portable from the world of art into science.”

“And I think that’s why the fashion brands love us,” she continues, “because they know that as artists, we value craft and quality, and a deep, intimate relation to the material — and also making something beautiful, not just something that’s high-tech.”

On a rainy New York City day in late March, sheets of what appear to be leather hang on the wall of one Chelsea art gallery, sleek black draped over tawny and beige. “I like to put out these samples because there’s so much variation that we can design for,” MycoWorks co-founder and chief of culture Sophia Wang tells Entrepreneur. “You could go for something very homogenous, or you could go for something that actually brings out the signature unique grain.”

A table sits laden with traditional leatherworking tools: sharp, wooden-handled instruments, a heavy press poised to set snaps and rivets. The tools, Wang says, allow artisans to “seamlessly” manipulate the material as they would traditional leather. Because, as much as the sheets on the wall look and feel like the real deal, they aren’t made from animal skin at all — though they are grown from living material: fungi, to be exact.

MycoWorks’ interactive “Freedom of Creation” exhibit tells the story of the biotech company behind Fine Mycelium, a natural, made-to-order material made from the root structure of reishi mushrooms. The company counts celebrities Natalie Portman and John Legend among its investors, and its mycelium material has already been adopted by major fashion houses such as Hermès. In fact, MycoWorks has outgrown its Emeryville, California pilot plant, which processes thousands of the mushroom-derived sheets per year; its new Columbia, South Carolina facility will process several million.